- Home

- Prayaag Akbar

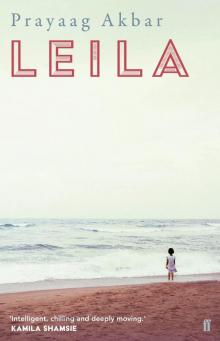

Leila

Leila Read online

LEILA

A Novel

Prayaag Akbar

For Amma and Abba

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

THE WALL

TOWERS

MA AND PAPA

CENTRE OF HIS PALM

WATER

PURITY CAMP

POLAR NIGHT

FORBIDDEN FRUIT

SETTLEMENT

SAPNA

THINGS THAT PULL US TOGETHER

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

THE WALL

My husband thinks we cannot find her. His voice is raw from screaming. ‘When will you understand, Shalini? It’s been sixteen years.’

‘You think I don’t know?’

Riz looks at me, bobbles his head but doesn’t say anything. In the sinking light his old-man stubble glitters like salt grain. It is he who doesn’t understand. I’m almost there.

As we walk from the broad pavement to a small rectangle of grass he pulls out two candles from the satchel. Purity One stretches out across us to the edges of the dusk, either end into the swirling ash. Gritty grey brick. Sixty feet high. Wrapping around the political quarter, sealing off the broad, tree-lined avenues, the colonial bungalows, the Ministries, the old Turkic gardens.

Standing where we are now the wall is shimmering. Broad iridescent streaks, shifting in the way green and brilliant purple dance on the throat of a pigeon. (Pigeons infest this place.) Purity One is believed to have an inscrutable power. People come here to pray and plead. Take my own situation. I should be standing alone, yet here Riz is, by my side, etched sharp against the dusk as anything around us.

Not far from where we are there is a small room abutting the wall. On the roof a white flag flutters, black pyramid, white tip. Hundreds of people shoulder past each other to get to this room. In the great heave all we see is a trapezoid of blue light where the double door extends above the devotees. There is a low cage in the room that everyone surges towards, diving to the ground with half-bleats and cries. Behind the thin wire bars is the holy centre of the wall: middle of the lowest line of bricks, painted ochrelike red. They worship this brick. They call it the first brick of Purity One.

Riz knelt to dig a hole in the earth. His back is badly hunched. Once there was a curving furrow of pebble-like muscles under each shoulder blade from hours every day on the squash court, but now, bent over the ground, he looked as a tortoise does when it retreats into its shell.

I got down beside him, creaky myself. ‘These are different candles,’ I said, rolling one about my palm. Thicker, a spiral design wrapping neatly around the white wax.

‘I found them near work. More expensive, but what the hell. It’s her birthday.’ He gave a tired smile. ‘Smell them. I think she’d like this smell.’

We come to the wall every year on Leila’s birthday.

A karate teacher waddled a file of white-kitted children to an emptier stretch. Within touching distance of the wall they stopped and bowed. A woman in a sequined burqa was talking quietly with her daughters. One of the girls was in a purple headscarf with a scalloped hem, while the younger, perhaps not of age, was dressed in a T-shirt and tiered skirt. They inserted prayers written on scraps of paper into gaps between the bricks.

We brought out a plastic shovel from Riz’s bag. Along the yellow scoop the plastic had frayed and turned pasty white. The shovel was part of a set we’d bought Leila before a beach holiday. It had a sticker on the bucket, of a bear sliding down a rainbow, that she’d pick at. We bring the shovel every year but it’s too blunt, too flimsy for the dry, tight soil of this patch of cratered green, the real work is done with our fingers. Soon we had holes two inches deep. We stood our candles in the earth. Packed the cavities with soil. Twenty minutes we sat and around us a scatter of bent and blacked sticks grew as the wind time and again guttered the candles. Everywhere else the stench overwhelms. It hits you in the stomach. No one seems able to do anything. Sometimes you see Slummers wading through the garbage, looking for things to sell.

A huge cheer went up. Two young men were visible above the thicket of heads, attempting the wall. They wore only white nylon basketball shorts with oilskin pouches tied at their chests, moving with upward pounces at unnerving speed, backs, calves, arms twitching and tensing, bodies bending double and right around like jackknives. One of the men was very dark-skinned. The other had a tuft of hair in the middle of his back. With the tips of fingers and bare toes they’d get a hold in the minute crannies and ledges between the uneven bricks, swinging higher all the time. The mob hummed with reverence.

‘How strong, to leverage their bodies this way,’ I said.

‘It doesn’t seem possible,’ Riz replied. ‘This sheer face. How are they doing it?’

‘Why not. Like those guys who pull giant chariots by themselves with metal hooks buried into their backs.’

‘Or the Shias. Whipping themselves to mush.’

The dark man tensed into a crouch and sprung to a jutting brick above. He couldn’t grab on. As he fell through the air he hammered the wall with his fingertips, striking like a snake at its surface. On the fourth attempt the fingers stuck. His shoulder wrenched and his body twisted but he clung on with a soft, stifled cry. We exhaled as one. He swung like a pendulum from one hand, grinning down at us unflustered, until he found a niche for his other. Extending his legs, he swung them up over his head so now he was upside down, biceps bursting, lank hair falling in perfect glistening straights like granite rain. He took a foothold and pulled himself upright. Relief in the cheering now.

When I dream about Leila she is always in the distance, outside the light, but I know she has a warm, open face. I still see her eyes, light like my mother’s, irises warm gold-brown pools in which the sun set ablaze radial chips of malachite, green and faintly black. She is impatient to meet the world, my little girl grown. She is taller than me. This makes me so happy. Sometimes she’s in school uniform, walking toe-heel, toe-heel, back arched, the proud shoulders and strong nose of all the women in our family.

Today she turned nineteen. Desires, insecurities, angers that I know nothing of, though I must’ve played my part in. I would know so little about her now. Maybe her laugh. When she was an infant I’d bring my face right to her nose and make a funny sound – ‘khwaaishhh’ – and she’d squirm with delight, cackling with a deep, cadent lilt. Her laughter now will carry a kernel of that. So I come here on her birthday. To ask her for forgiveness. We didn’t respect these walls, so they took her from me. Sixteen years. Does she wonder sometimes where I am? If I abandoned her? I’ve read the books. She won’t remember. She was taken on her birthday, only three years old, so she doesn’t, can’t, remember. When I think about this, it’s like I’m burning on the inside. She wouldn’t know me if we crossed on the road.

To her I am an emptiness, an ache she cannot understand but yearns to fill. No. I have left more, a glimmer at least. The blurred outline of a face. A tracery of scent. The weight of fingertips on her cheek. The warmth of her first cradle, my arms. I found a journal on early cognition in the library. One article said our first memories go back to two and a few months. We don’t remember how things flow into each other, how they are linked, but our minds can place, in the vast fog, discrete islands. Maybe she remembers accompanying me to the mall one winter morning, white-frame sunglasses on her head. A Santa greeting the customers walking in. Leila so thrilled by this her shoulders began to vibrate. She squeezed my hand, still trembling, tugging gently until we stepped out of the security-check line.

I could see only his unfitness. Thin-limbed, dark-skinned, sweating in the hard noon sun. Over the double doors forlorn clumps of cotton glued to the lintel. Peach foundation tr

ickling down his forehead like muddy rain down a window. But Leila was transported. She ran to him, mindless of the stale, cheap duvetyne, its acrid whiff. She was laughing and he pinched her cheek between his hairy knuckles. I didn’t say a word.

‘You want a present from Santa?’ I finally asked. There were gift-wrapped boxes piled against the front window, clearly empty.

Leila looked confused by this. Maybe she didn’t know what Santa did. The suit, the beard, an image in some book come to life, this was what thrilled her. The burden of age is expectation. It leaves a judging eye. She turned to me and smiled in a lopsided way, as if suddenly aware of her excitement, and when I saw her expression, that gentle glint, I felt her elation as if it were growing within me. Of course this place was enough. There was charm to be found here, there was nothing tacky. My baby’s full-beam happiness at its centre, and I as innocent as her, as untroubled.

All this. Why do I fool myself? Leila will remember something quite different, if she remembers anything at all.

*

We gathered our things. The wicks had almost touched the ground. Riz’s flame shivered for a few seconds in the wind and then gave up as well. I’ve come here every birthday since we lost her. There will be thirty-two candle stubs buried about this little lawn. When I find Leila I will dig up each one.

The dark man was struggling. This wasn’t a race, the route up too tricky, still the air was fevered, an elemental rivalry. The men represented different lower orders. You don’t see the high communities at street level very often, only on festivals. Around us garbage lay strewn, claiming the pavement, paper, matter, polythene fusing wetly into grime. In the shadows the trash had mounded and the long mouths of wandering livestock burrowed deep. The air so thick that with every breath I could feel a sediment, something black and gritty settling in my chest.

A wet yell. The other man had made it past the last of the handprints, only twenty feet from the top. At his knees gleamed the last red splotch. Fingers carefully splayed, the square palm defined. He made two more movements, rising a few feet. Holding on with his toes and one hand, this man tugged at the thread around his chest until the mouth of the oilskin pouch had loosened enough to dip his right hand inside. He pulled his hand out, holding a bright red palm aloft to wild cheers. He thrust his hand against the wall with a sense of theatre, pressing down from every angle like a rolling press. The highest anyone had gone. As the crowd continued to cheer he began the climb down.

The dark man was ten feet below, stuck. He cast about desperately for a gap in the brick face. Red handprints fanned out around him. This was as high as most got. The mob had shifted in mood. Some people began to hoot, which turned into a chant. Finally he lunged. From his slumped shoulders it seemed he knew he wouldn’t make it. He grabbed with his left hand but clutched at nothing, seeming to bounce back off the wall, not falling along the face but arcing out, ever further from the bricks as he dropped. The crowd braced for impact. He fell directly into the mass of people. In unison everyone took a single step back, like ripples in a pond, and there was a sickening crack, a seamless farrackfatfat like the sudden spit of a log fire. It wasn’t clear if the crowd had broken his fall, as it was supposed to. We turned quickly and walked away.

*

Riz died the same night they took our daughter. Yet here he is, by my side, as I walk from the wall to the huge field where our old school, Yellowstone, used to be. It’s like this every year. On Leila’s birthday he comes back, sharper here than anywhere else. He has grown old with me, my loving husband. This stoop and granulated stubble, the slowed walk, the dull coin of scalp showing at the crown. He was twenty-eight when he died. Why does he look older? Maybe I find him as I need. Maybe it is something else.

Tonight is auspicious, a rare alignment of moon and planet, star and node. There will be a display at the field too. We walked together through a parking lot and gully with overlays of political graffiti on either side before turning onto a main road. No one else walked here. It’s the rancid smell, and the rats, big as cats, scuttling out from the garbage and scampering hairily over your feet. Most people take the long route. All the way down this road there is a dense, growing pile of trash that has shaped over the years into an incline covering half the street. Festering peels, thick trickles of fluid, unidentifiable patches of white and yellow, bulging plastic packets breached at the gut, oozing. Soaked, blackened rag-like emanations, long as dupattas, fished out from blocked sewers by scavenger-caste men who dive in little chaddhis into manholes. The smell was so bad we trotted, almost jogging, as we followed the curve of the road. Just then a huge grinding and crashing. A massive gate built in the upper half of the wall slowly retracted, joining the network of flyroads way over our heads. The wet amber eyes of passing cars blinked out in procession into the darkness.

Riz had his neck craned back. Still his jaw hung slightly slack. ‘These flyroads are everywhere now,’ he said. ‘Throughout the city.’ He pointed to a node in the distance. Three flyroads came together in long concrete sweeps, lifted to their magnificent height by grey pillars, broad and round, anchored deep in the concrete ground. ‘They link into one another,’ he said.

‘How else will they get around? Can you imagine Dipanita or Nakul, any of our friends, if they had to see all this?

‘“It’s so filthy down here!

‘“I thought all this was over.

‘“Must they bathe on the footpath like that? It’s like they have no shame left.”’

Riz’s smile glimmered in the darkness.

I’ve never been on a flyroad. I’ve heard it’s different to drive around up there. Easier to breathe. The air doesn’t pick at your eyes, as it does down here, all day secretly seeping through your lids, by evening the rim around each eye inflamed. We turned a corner. For this last stretch no wall loomed over us and there was a glow in the sky like bouncing blue fire. Music; incantations set to pounding beats. The road ends at what used to be a large cricket field. You can still see half a burnt-down scoreboard with the Yellowstone crest and motto. Riz and I met in this school. This was where we wanted Leila to go.

Thousands of people stood on the old cricket field. People danced, prayed, sang and chanted, drums pounding, around small fires, a mad tumult that had something of the swell and fetch of an ocean. Motorbikes ripped up and down each zone with young men whirling the flags of their community. Yet one circle near the centre was almost empty. White velvet on the walls, white carpeting. Big cars coming off the flyroads arrived into this empty patch and as soon as each docked the driver leapt out. A family would emerge from the back seat and slowly, to show respect, walk the length of the zone to the stage. Once they had made their offering and touched the man-god’s feet they walked back, climbed into their cars, were driven away.

The man-god, a gristly beard over a flowing gown, waistcoat of gold embroidery, stood centre stage, on either side ladies with thaalis in their hands. They had tied their saris low on the waist. As he canted into the microphone the women pulsed their shoulders. The music changed and they began to dance, bending at the waist from side to side, towards him, away from him.

‘Is this it – the culture they wanted?’ Riz suddenly asked. He is angry. He doesn’t take heart from the search, as I do.

Moths and gadflies flutter into our faces as they race to the stage lights, dazed, convinced they’d finally found the moon. Wolf whistles cut through the electronic dholaks and rhinal singing coming from the elaborate arrangement of outdoor speakers. The top layer of speakers slicked blue from the stage lights. The audience dances on, thrusting elbows and crotches, clinging off one another and leaping about.

On stage, two dancers carried out massive wicker baskets. They placed them at the front of the stage and retreated to a safe distance. The audience started to throw metal objects at the baskets – copper bracelets, silver rings, earrings, necklaces, amulets, buckles. The outer sectors were competing. When the baskets brimmed with dull metal the man-god walked to the

front and extended his arms. Everyone seemed to stop, a hush fell over the watchers, like a tablecloth that snaps in the air and slowly descends. Four men in black T-shirts emerged to carry the baskets centre stage. The man-god began to swing his arms in alternating circles, finding the rhythm, faster as the tempo rose. Thick arms whirred into a blur as the beat climbed. The air gathered up, suddenly thicker. Then the lights went off, only the purple glow from a cylindrical blacklight found the man-god’s gold waistcoat, and at this the audience combusted, a hysteric peal that rolled around the crowd like the skirt of a dervish. The man-god stopped. Perfectly still, he let out a long, high yell. The lights came back on. Both baskets were filled now with gold.

The applause was deafening. As the four men carried the baskets off-stage, Riz shouted into my ear, ‘All I can remember is how beautiful this place used to be. Coming here every lunch. I still see you in that school dress. That silly belt.’

Maybe we have the same conversation every year. ‘Have I told you,’ I asked, ‘what I think of when we come here? The day I came for Leila’s admission. We were lined up in front of that gate. It would’ve been there, where that man in the white shirt is standing – there with his legs crossed. It was so hot that morning the school windows shone like silver foil.’

‘Wasn’t this the long summer?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

I was nervous that day. I distracted myself by counting how many women waiting in line with me seemed to glint in the open sun. Their phones and fingers, earrings and oversize sunglasses. It was only mid-morning but a serious heat powered down. Dust devils roamed the parking lot. The birds were long gone, the trees naked of leaves. Everyone in line fidgeted as sweat sprang from awkward places. We weren’t used to being outside. ‘One by one, mothers and fathers trooped back,’ I whispered to Riz. ‘How scared I was when I reached the front. Running down the lists stapled to the bulletin board behind the gate. Then I saw her name. Two years, ten months. Your name alongside.’

Leila

Leila